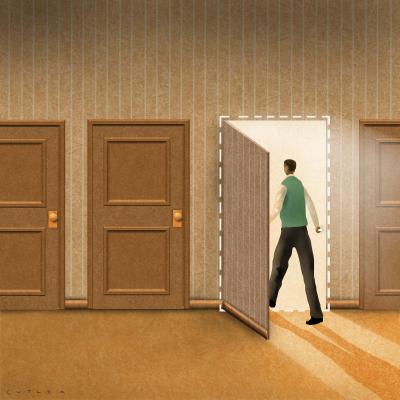

The joy of steering your interests toward something completely different

“When was the last time you did something for the first time? When was the first time you did something for the last time?” Those questions are tacked to the wall of my office. I have, at certain times in my life, received odd bits of wisdom; they all end up on the wall. A cartoon acquired at my first job depicts a sign on a muddy road warning: “Choose your rut carefully. You’ll be in it for the next 18 miles.” My editor had given it to me. When I would complain about a certain task, he would say: “How you deal with boredom may be the most defining of character traits.”

That became one of my core principles: One should always be on a learning curve. It helped that my job demanded discovery. As a writer, I explored new topics every month. The rut I chose lasted 40 years.

To be on the learning curve you must be willing to be a beginner again, to wrestle with skills not entirely under your control.

Illustration by Dave Cutler

And then it disappeared.

I thought I was prepared. I had the notion that before you retire, you should have three passions on call, three irons in the fire, to fill the sudden abundance of time. I decided to devote more effort to photography; to reread One Hundred Years of Solitude and every mystery by Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler; and to learn the guitar riff or the first 10 bars of every Beatles song. (OK, maybe just the ones in the key of E.)

I soon discovered the flaw behind to-do lists. When the list is accomplished, you hit a “now what?” moment. I had simply spent more time indulging existing talents and interests. And none of those goals took me out of the house, involved other people, or kept me connected. I was no longer taking risks.

The learning curve, I realized, should lead somewhere.

A friend who took up online dating apparently mixed up his likes and dislikes in his profile. It took him months to notice that the women he was meeting were drawing him into activities he had previously avoided – and that he was enjoying himself.

Something similar happened to me. My likes had brought me this far in life, but what did I know? I met a woman who loved jazz. Before then, I owned maybe three albums of music without words. A year later, my listening now includes Anat Cohen on clarinet, Wes Montgomery and Bobby Broom on jazz guitar, Wynton Marsalis. I sat in the balcony of Chicago’s Orchestra Hall and watched 77-year-old McCoy Tyner grab handfuls of heaven on the piano, delivering an entire lifetime in a single evening. I discovered the American songbook, came to appreciate the phrasing, the power of a single word. Nina Simone. Billie Holiday. The continuing education changed my map of Chicago, my hometown. I discovered the Green Mill, a jazz club that had been a speakeasy in Al Capone’s era.

The learning curve should lead you out of the house.

I am not a foodie, but in the past year I have eaten at 35 restaurants that were not Cross-Rhodes, the Greek place that was the go-to choice for my kids for 20 years. All in the company of friends, old or new. Ted Fishman, author of Shock of Gray, a book on aging, pointed out that people who adopted the Mediterranean diet, hoping to live longer, were missing the point. In those cultures, breakfast, coffee, lunch, wine, and dinner all happen in the company of other people. Conversation is as important as the nature of calories consumed. Visit a café in Rome: What you notice first is that no one is talking on a phone. They are lost in face-to-face conversations.

The experts recommend learning a musical instrument but say that practicing something you already know doesn’t count. I was a child of the folk scare of the ’60s, so I play acoustic guitar. But I seldom ventured above the fifth fret, and I never bent a note. I belonged to the “learn three chords, play 10,000 songs” school. Suddenly my hands were attempting jazz chords (learn 10,000 chords, play three songs). My hands sometimes cramp up in a Dr. Strangelove spasm. A concerned friend asked, “What’s that?” I responded, “Oh, a D augmented 9th or maybe a G13.”

I have a friend who decided, out of the blue, to learn stand-up bass. He mastered the instrument, formed a jazz quartet with a killer vocalist, and now plays at clubs and galleries around Chicago.

I met a woman who, after working as an emergency room physician for decades, developed a passion for tango. She takes lessons three nights a week. She travels to tango festivals and has gone to Argentina to work with legendary dancers. She owns multiple pairs of shoes with heels cut to different heights to perfectly match her partners. And you thought golf was equipment-intensive.

A friend asked one day if I would be interested in an afternoon listening to Israeli voices, people telling stories about their experiences on a kibbutz, about attending school, about finding love on the streets of Jerusalem. Why not? One story haunted me for weeks. What was going on? I usually forget the plot of a movie by the time I validate parking.

I discovered that Chicago is home to a major storytelling community, one you can find in a bar or on a stage every night of the week. This, too, changed my map of the city. I have attended Moth “story slams” from the South Side to the North Shore, sat in intimate Irish pubs being moved to laughter or tears or heartache by the sound of human voices.

Find a microphone. Tell your story. This campfire has been burning for millennia. It is human connection in its purest form, the exact opposite of what often happens in social media.

On a visit to Alaska, I talked to a woman in a tiny fishing village. I asked her what she did for entertainment. “I watch the yard war. That plant over there has been trying to take over.” A close friend and fellow writer, Craig Vetter, talked about the joy of watching the earth speak, pushing out words that mean carrot or blueberry or lettuce.

For most of my life I was inclined toward adrenaline sports, velocity. Then I inherited a garden. Over the past few years I have built a vocabulary and a library of reference books. I’ve started a calendar, photographing the arrival of bluebells, lilies, wood anemones, lobelias, bleeding hearts, astilbes. If this is July, that must be echinacea. I have seen plants change in the course of a day. I have sat in the backyard watching the fireflies rise.

I once met a college professor who upon retiring decided to learn Spanish. He had looked at the changing demographic of his home state and realized that to reach out to these new citizens, he would have to speak more than his native tongue. It was a form of greeting, of welcome, a skill that would allow him to continue to teach and to share. I witnessed a brief exchange – we may have been gutting houses after Hurricane Katrina – that gave me a glimpse of applied knowledge.

I’ve known people who decided to learn Italian describe the pleasure of ordering a cappuccino on a plaza in Rome, the joy of being able to tell a laundry in Venice how they wanted their shirts done, the thrill of haggling for vegetables in a market halfway around the world. My next-door neighbor, who has spent his life learning dead languages and sorting through translations of the Old Testament, started taking French lessons from Monique, an 83-year-old neighbor, in exchange for shoveling her sidewalk in the winter. To his delight he found that following a single phrase as it tumbles through the centuries is to make the past a living creature.

To be on the learning curve you must be willing to be a beginner again, to wrestle with skills not entirely under your control. As we age, this will prove helpful.

In 1990, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi pioneered the psychology of optimal experience, studying the mental state of people focused on doing one thing well – rock climbers, surgeons, dancers, musicians. He found that facing a challenge ignited the brain. In his book Flow, he noted that most of life is made up of everyday activities – dressing, shaving, bathing, eating – that require almost no concentration. You can fly on autopilot or indulge in guilty pleasures – binge-watching entire seasons of Downton Abbey, Dexter, or Breaking Bad, completing the New York Times crossword puzzle in record time. But to attain flow – a state of full engagement, focus, and enjoyment – you have to tackle challenges that are just beyond your abilities, that are new.

Concentration – undivided attention – is a powerful human force and a source of joy and fulfillment. Use it.

-- James Petersen is a freelance writer, full-time storyteller, gardener, guitarist, motorcyclist, and now a grandfather.

• Read more stories from The Rotarian