Rotarians in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, USA, tout their town as baseball's true birthplace

If you’re a baseball fan, you probably think of Cooperstown, N.Y., as the game’s birthplace. That’s why the Hall of Fame is there, right?

But the Cooperstown story is a myth. The Hall of Fame itself refers to the “mythical first game” there. That first ballgame, supposedly played in 1839, is the sort of alternative fact the New York American sportswriter Damon Runyon called “the old phonus balonus.

So where did baseball really start?

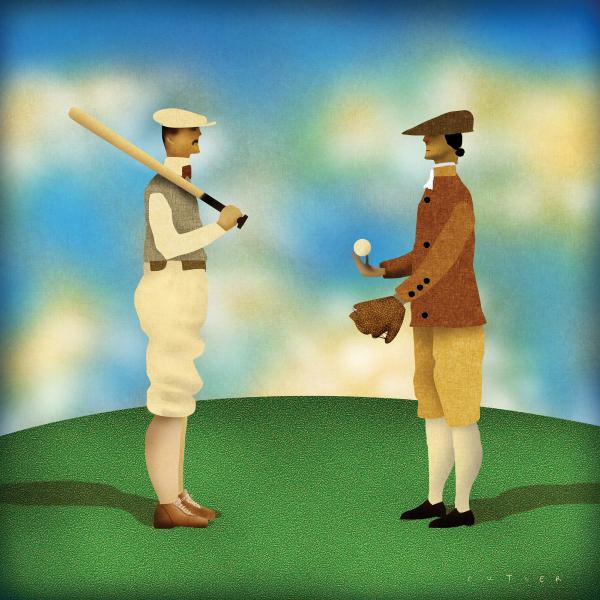

Illustration by Dave Cutler

“Right here,” says Phil Massery, pointing at the turf beneath his feet. We’re at Rotary Park in Pittsfield, a cozy town in western Massachusetts, USA. He and 30 other Rotarians are enjoying a summer barbecue in lieu of their usual meeting at a hotel. The park, with its playground built by Massery and other members of the Pittsfield club, adjoins a Little League diamond.

Wherever you go in Pittsfield, baseball is nearby.

“I’ve got nothing against Cooperstown,” Massery says, “but people should know the Hall of Fame is there by mistake.” He laughs. “I doubt they’ll move it here, though.”

Sitting in the shade with library director Alex Reczkowski, insurance agent John Murphy, and other local leaders, Massery, a real estate broker, tells the true story of baseball’s history. “It starts with Cooperstown, all right, but not the way people think.” Back in 1904, sporting goods tycoon Albert Spalding named a panel of experts to determine how the national pastime had begun. But Spalding didn’t want to hear that the sport had evolved from English games such as cricket and rounders. He said – and this is a direct quote – “Our good old American game of baseball must have an American Dad.” So it got one. The panel declared that Civil War Gen. Abner Doubleday invented baseball in Cooperstown in 1839. Never mind that Doubleday was a plebe at West Point at the time. Never mind that Doubleday never claimed to have anything to do with inventing baseball. (One historian wrote that the man “didn’t know a baseball from a kumquat.”) Fans and sportswriters bought the story, and the Hall of Fame opened in Cooperstown in 1939 to mark the 100th anniversary of the First Game that never was.

“Now flash-forward 65 years,” Massery says. In 2004 John Thorn, Major League Baseball’s official historian, discovered a document written in Pittsfield in 1791. “George Washington was president. There were still only 13 states. But there was already baseball here in Pittsfield. How do we know? Because kids were knocking windows out of the town church!”

City fathers didn’t want rocks, horsehide-covered balls, or anything else pocking the First Congregational meetinghouse. They had paid Charles Bulfinch, the architect who was about to design the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C., to build it. So they passed a local law. “For the Preservation of the Windows in the New Meeting House,” it read, “no Person, an Inhabitant of said Town, shall be permitted to play at any Game called Wicket, Cricket, Baseball … or any other Game or Games with Balls within the Distance of Eighty Yards.” This was the first known mention of the national game in American history. As Thorn announced at a press conference, “It’s clear that not only was baseball played here in 1791, but it was rampant.”

A Hall of Fame spokesman called the discovery “incredibly monumental.”

“Pittsfield,” crowed then-Mayor James Ruberto, “is baseball’s Garden of Eden.”

George Washington was president. There were still only 13 states. But there was already baseball here in Pittsfield. How do we know? Because kids were knocking windows out of the town church!

Today the Rotary club holds its regular meetings at a hotel a block from Park Square. It’s a long fly ball from there to the spot where schoolkids played 226 years ago. In those days, Park Square was a grassy block at the crossing of the town’s main roads. It would have taken quite a clout to launch a ball from there to the meetinghouse. You would think such a shot might earn a kid a hip-hip-hooray. But the descendants of the Puritans frowned on such displays, so we can imagine the young Pittsfielders pioneering something like today’s walk-off home run. Somebody smacks a long one, they all wait for the sound of breaking glass and run off as fast as they can.

What was the game like in those days? “The basepaths would have been shorter than they are today,” says historian Thorn. “The ball would be smaller than the one we’re used to, and softer. Fielders would throw base runners out by ‘soaking’ them – hitting them with the ball.”

More than two centuries later, Park Square is a leafy ellipse in the middle of a busy traffic circle. It’s a couple hundred feet from there to the towering First Church of Christ on the site of the old meetinghouse and the small plaque beside the church. ON THIS SITE IN 1791, it reads, A NEW MEETING HOUSE OF THE FIRST CONGREGATIONAL PARISH IN PITTSFIELD WAS BEING COMPLETED WHEN SEVERAL OF ITS WINDOWS WERE BROKEN AS A RESULT OF BALL GAMES. But few visitors notice the plaque. Even among people born and raised here, as Massery was, few know that Park Square is a special place.

“That’s our own fault,” he says. “We haven’t done enough to get the word out.”

At the barbecue, talk turns to baseball. Club President Jeff Hassett recalls his dad’s days running the local Babe Ruth League. Another Rotarian remembers his Little League years, when his coach said that “we had a tradition to uphold – years and years of Pittsfield baseball. Thousands of years, I thought. Maybe millions. I was 12!” Reczkowski mentions that the library he runs is where the 1791 document was found. “We’ve got it in a vault,” says the library director, who knows his local lore. “Our minor league diamond, Wahconah Park, is one of only two in America that face west. Did you know that? It means that the batter looks right into the late-afternoon sun. We’ve got a park that has rain delays and sun delays. And our team, of course, is called the Suns.”

Of course they all know why other ballparks face east. It’s so the batter has the afternoon sun behind him. That means the pitcher faces west, which is why left-handers are called southpaws.

Eric Schaffer used to watch his beloved Chicago Cubs on jumbo screens in Las Vegas casinos. Schaffer, who moved east with his Pittsfield-born wife 20 years ago, likes the “baseball feel” of New England and the regular-folks vibe of the local Rotary club. “It’s nice and casual here,” he says. “Plus the fines aren’t so bad. My cell goes off at a meeting in Pittsfield, OK, I’ll pay a dollar. The Vegas Rotary met at Harrah’s – there were some high rollers in that club. My phone went off in Vegas and it was, ‘Schaffer, that’s a $100 fine.’”

He and Massery and the others agree that Pittsfield could use an extra dose of pilgrims’ pride. “We should be one of the capitals of baseball,” Massery says. “I’m not saying the capital, but we really should be better known.”

The Hall of Fame at Cooperstown now recognizes Pittsfield, displaying a copy of the 1791 document near the front door. Serious fans know about the game’s roots in Pittsfield. “So why aren’t we capitalizing on it?” Massery asks. He did his part by paying for hundreds of baseball caps emblazoned “1791.” Local Rotarians wear them. But now he’s thinking bigger. He has his eyes on an abandoned building downtown. “We could turn it into a tourist attraction, our own little hall of fame.”

And what if someone finds evidence of a still-earlier baseball game? Wouldn’t that spoil everything?

“I feel good about our claim to fame. We got a lot of attention when the document turned up. Since then, every town in New England has had 13 years to rummage through its records. If they were going to beat us, they’d have done it by now.”

• Kevin Cook is a member of the Rotary club of Northampton, Massachusetts, USA, and a frequent contributor to The Rotarian. His latest book, "Electric October," is about the epic 1947 World Series.